Ask any Black, Indigenous, person of colour (BIPOC), and they will tell you about the first time they experienced a racial divide: the moment when a single event propelled them from the safety of belonging into a place of shame, discomfort, and disconnection.

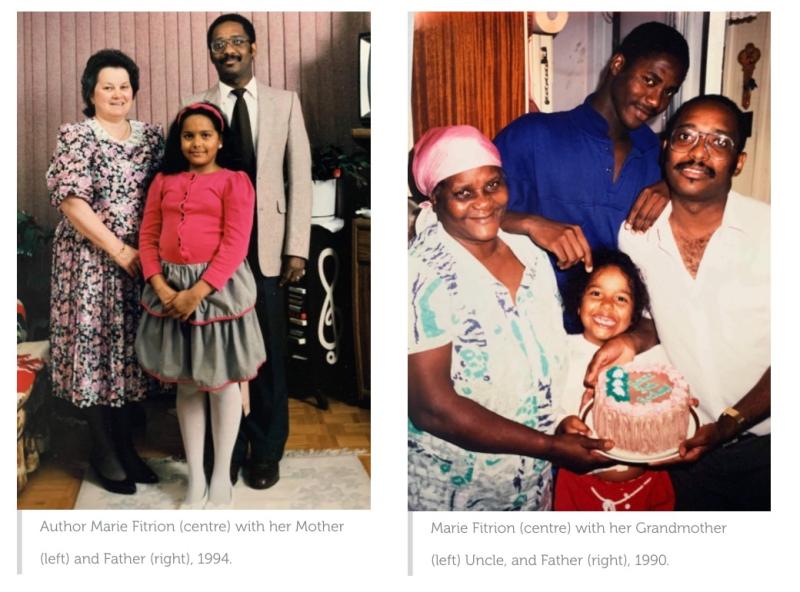

For me, it happened at age six. My mother befriended a co-worker who had an eleven-year-old daughter. Naturally, our parents believed we’d become fast friends. During her twelfth birthday party, I overheard her and her friends laughing about how “dirty” my brown skin looked. They went on to say that the dress I was wearing (which originally belonged to the birthday girl) looked better on her skin colour. I was the only person of colour in the room, and for the first time, I associated my race with something negative about myself. More than thirty years later, I wish I could hug that frightened little girl and help her navigate through the difficult journey ahead. I would speak openly to her about race and the unique challenges of being biracial, and help her to love and understand her racialized self. This five-part series is dedicated to my inner child. It stands as an invitation to those who want to consciously explore race and race-related issues, from selfhood and interracial dating to celebrations and raising children.

Embracing BIPOC identity

Your family provides a baseline for you to see and experience the traditions, cultures and languages that make up who you are. For me, this meant building a Black identity that influenced the food I ate, the music I listened to, and the languages I spoke. In the 90’s, when I was growing up in Barrie, the world beyond my house was a very homogenous white community that, at best, ignored my race, and at worse weaponized it to paint me in a negative light. At home I operated in a racial cocoon which validated my identity. But when I began to interact with my peers, I felt unable to share my experiences with them. I slowly began shying away from my differences to embrace more mainstream attitudes and ideals. While I no longer feel this disconnect, I know that I am not alone in experiencing these feelings of alienation in my youth.

Wanting to understand more about my experience, I spoke to Toronto-based psychotherapist Moin Subhani, co-founder of Love Evolution, who specializes in providing therapy for BIPOC, immigrants, and second-generation children. Subhani sees the transition I described as part of a big-picture journey that begins as a child and continues well into adulthood.

“The act of becoming your whole self is a journey that requires love, empathy and compassion for others and yourself,” says Subhani. “It’s not a linear path, as different stages may occur in different aspects of life (career, relationship, political, etc.). It’s all about reframing how we see ourselves and having the tools to respond to those changes.”

Identifying with the Colonizer

In this stage, individuals may consciously or unconsciously downplay elements of their “otherness” to fit in. It’s not unlike how many children and teens cope with their sense of self in their formative years. However, for BIPOC groups, their connection to themselves and their families can add an additional level of strain to these relationships, and lead to a lack of internal harmony. While this can be a useful stage to revert to when starting a new job or attending a social gathering, it’s essential to recognize how detrimental this can be in the long term. Personal growth and development requires us to look at ourselves and our histories without fear of persecution. Moving forward can be difficult when shame, combined with a desire to belong, makes band-aid solutions alluring.

As a native French speaker who attended a French-language school, I tried very hard not to have an accent when speaking English as a child. I studied TV characters, mimicking their diction and vocabulary until my faint French accent disappeared, replaced with a California-style English right out of Bayside High! I now recognize that this small act was rooted in fear, and that assimilation felt like the only reasonable choice. At the same time, the outcome of this self-conditioning is also, in part, a privilege I now possess. I am reminded of this every time someone tells me I speak English very well, and with no accent. I make a point to say that accents reflect what you hear around you, and are not a marker of linguistic comprehension. Had my parents chosen to speak to me in English at home, I could have easily picked up their accent. My ability to walk into most rooms without having my mastery of a language challenged is something many first- and second-generation immigrants are not afforded.

Identifying with the Colonized

In this stage, individuals may make a dramatic shift to the opposite end of the spectrum, rejecting norms and expectations assumed to be universal and true. Often, this stage arrives once individuals feel safe and supported enough to begin breaking away from their peer group, and establishing (or re-establishing) themselves within their own unique parameters. Revisiting childhood traditions, appreciating art, or finding and creating connections between culture and lived experience can be a profoundly cathartic task.

“White ideals no longer tyrannize you; in fact, you want to turn those values on its head,” says Subhani. “It’s a celebration of the rejection and rejoicing of that which was considered wretched. There’s a quality of falling in love or coming home, where the person feels reunited with themselves.” I remember being in this state, looking at my brown skin, and being overwhelmed by its beauty.

For some, identifying with the colonized can be a jumping-off point for letting go of grief, and an opportunity to begin the healing process by rebuilding a connection with the community. It is here that many of us find ourselves in 2020, grappling not only with a global pandemic, but with police brutality, white supremacy, and systemic racism. Maintaining current conditions has become exhausting for many of us who are unwilling to continue with the status quo during a time of crisis.

According to Black Mental Health Canada, Black immigrants and South Asian males are more likely to develop moderate to high mental distress than any other ethnicity.’While mental health stigmas are still quite prevalent in these communities, newer generations are changing this narrative and leaning into the positive effects that seeking mental health support can have in their lives.

For others, surrounded by a supportive community and rooted in a sense of pride, worthiness, and belonging, this stage is a beautiful baseline. It is from this place that anti-racist work begins, where BIPOC claim space, and problematic ideologies are identified, discussed and dismantled.

Moving beyond the social construct

This stage is concerned with themes of sovereignty and transcendence, during which we recognize that race is a social construct, and that classifying each other in this way is both limiting and inaccurate. As a biracial person of colour, I often reflect on how dogmatic definitions of “race” will become increasingly irrelevant as more interracial children are born. It is not that we should ignore race, or choose not to see colour, but rather to honour each individual for their unique perspectives.

It is incorrect to assume that people who belong to one race or another are monolithic or identical. The goals are moving past stereotypes, educating ourselves about history, getting uncomfortable, learning about our own biases, and dismantling systems of oppression in our daily lives. It’s about recognizing that racism doesn’t need to be malicious to be effective. If we focus on practicing anti-racism through kindness, empathy, and respecting boundaries, we’re on the right path. Having experienced racism doesn’t make me an expert on it, but it does provide me with the motivation to ensure its presence is an outlier.

As you move through different scenarios in your life, recognizing these stages will foster patience and kindness with yourself. Exploring the racialized self is a continuous process. Each step forward is an act of love and an opportunity for you to create new boundaries for your relationships, friendships, and yourself.

EcoParent is committed to highlighting and amplifying diverse voices and perspectives. We want your stories to be heard and supported through our platform. We are listening, and we are learning. Please join us on social media to continue this dialogue @ecoparent.

This story is part of a five-part series on Consciously Exploring Race & Relationships. Sign up for our newsletter to have the latest articles on these and other topics of social concern sent to your email.